Learning new languages is one of the most rewarding endeavors I’ve ever decided to commit time to. Language is a reflection of people and culture. Getting to know other languages helps you better understand people and can unleash new ideas in your brain.

Mandarin and Taiwanese are my native tongues, although I’m far more fluent in English today. Every once in a while, I encounter phrases that I can’t translate. For example, 撒嬌 (sa jiao). There is no phrase in English which is an accurate translation. I’ll attempt in several sentences. It is a verb for females towards males, generally for the daughter/gf/wife towards the father/bf/husband. It is act of acting cutesy/lovable in an attempt to manipulate the man into doing something the female desires. Related words which come to mind are “spoiled” and “manipulative.” If you take a second to think about the implications of why it takes so many sentences to translate this innately Chinese concept into English, you start to see differences in the cultures from an angle you might not appreciate otherwise.

In Spanish and Portuguese (both Romantic languages), there are more precise verbs for “to be” than in English. I’m not very good at either, so bear with me. There are two verbs, “estar” and “ser”. Estar is more transient than ser. For example, “I am American” (Soy Americano/Sou Americano) uses ser – it’s not something that you can change. However, “I am sad” (Estoy triste/Estou triste) uses estar – since it’s a transient mood. Between Spanish and Portuguese, there are subtle differences, “Where is the bathroom” translates to “Dónde está el baño” (estar) and “Onde é o banheiro” (ser), respectively. It’s as if the Spanish have a more relativistic view of space than the Portuguese! I’m not sure I’ve come to any conclusion about why this difference exists, but it’s pretty interesting to think about.

As a tech geek, different languages are of interest in both practicality and curiosity. In my early years of programming, I often scoffed at people who would rave about the latest language in the interweb limelight. In my head, there wasn’t anything that could be programed in one language that couldn’t be done in another, after all, all (relevant) programming languages are Turing complete. It wasn’t until after I used Clojure in a non-trivial project that I truly started to appreciate the higher level benefits of some languages. The expressiveness in Clojure was just not something I could replicate in Java. Its beauty and concision allowed me to express and realize ideas that I wouldn’t have reached otherwise. As a default, I now think and prototype in Clojure just to get my head straight, even if the project requires that I deploy in (and thus need to translate to) another language.

Pretty wide range of thoughts, I know, but I think my point is that understanding and thinking in other languages – whether spoken or for programming – can provide a deeper understanding of the subject than otherwise possible. Plus, it makes traveling and programming more fun!

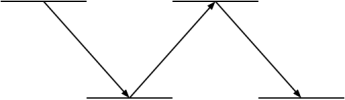

VS

VS